Savor your favorite dishes without food coma

by: Due Quach

The phrase “feast or famine” describes how I used to relate to food. As a kid, on the special occasions I was treated to my favorite dishes, I would compulsively eat it like it was my last meal on earth. If no one was watching me, I would eat the entire family sized amount all by myself. I would eat until I was so full, I couldn’t move and felt like I could die from bursting.

My entire life, I have had an irrational fear of running out of food. In hindsight, I suspect this fear and these compulsive eating tendencies could be linked to my family escaping from Vietnam when I was about six months old. I starved for several days when our boat ran out of food and experienced a long period of malnutrition during the one and a half years we lived in refugee camps in Indonesia before we were resettled in the United States.

As I grew older, I developed more self-control and realized my favorite foods were not disappearing. Being surrounded by an abundance of food meant that I did not have to gorge on them like there was no tomorrow. Furthermore, getting sick from overeating enough times forced me to learn the capacity of my stomach.

However, all these lessons flew out the window during the holidays. Something about the combination of holiday music and decorations, cold weather and snow, the rareness of gathering so many loved ones together, the specialness of holiday foods, having over-indulgence be socially sanctioned, and not wanting to waste any food would lead me to eat double, triple, or quadruple my normal meal size.

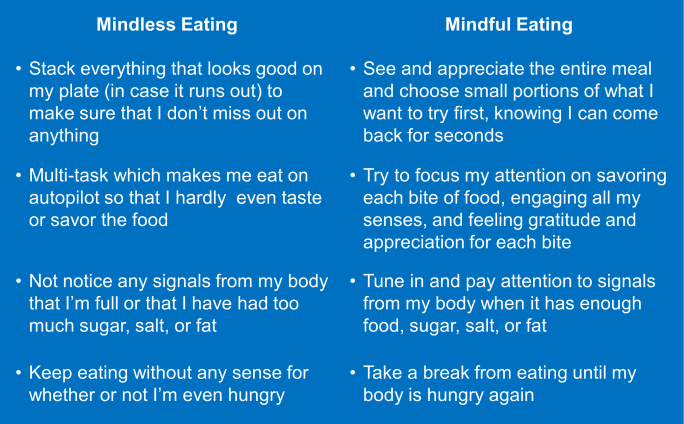

Learning mindfulness changed everything by helping me understand the difference between eating mindlessly and eating mindfully. See table below.

The key to mindful eating is to be able to observe when my mindless eating habits start to kick in and then consciously choose to come back to the mindful eating practice. If while eating, I start to multi-task–meaning watching TV, doing work, or thinking about something else–my autopilot will naturally take over the process of eating, activating hardwired eating habits so my mind can do something else. The only way to not eat on autopilot is to actually pay attention and be present for every step of the eating process.

Mindful eating helps us develop our capacity for interoception, which can be broadly defined as the ability to sense signals originating within the body and also interpret them. Basically, interoception enables us to answer the question “How do I feel?” The interoceptive system is made of special nerve receptors that enable us to sense and assess our physiological condition by tuning in to internal vital signs, such as respiration, heart rate, hunger, thirst, and the need to use the bathroom, as well as our energy levels and emotional state.

Interoception activates the vagus nerve, which serves as the superhighway by which internal organs send signals to the brain. The vagus nerve is a key part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs our “rest-and-digest” functions. Interestingly, the fight-or-flight response deactivates the vagus nerve (and the parasympathetic nervous system); conversely, activating the vagus nerve helps the body shift from fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest mode. So tuning in while we eat can increase the activity of the vagus nerve and enable the digestive system to function more optimally.

Instructions for mindful eating

When you begin, it helps to eat slowly so you can feel all the micro movements and sensations involved in each step of eating.

- Engage your senses: sight, smell, touch, taste, and sound:

- Notice what your food looks like with your eyes.

- Notice how it smells with your nose.

- Depending on what you are eating, if it makes sense, touch the food and notice its texture in your hands.

- Notice the initial flavor and the sound as you bite into it.

- Notice its texture in your mouth and how the texture changes as you chew.

- Notice how different flavors get released as you chew.

- Observe each step of the process. Notice what muscle movements are required for eating:

- How do your hands bring food to your mouth?

- How do your body and head move as you eat?

- How does your jaw work to bite and chew this particular food? How does the way you bite and chew vary with different types of food?

- How does your tongue work to taste food and move it around in your mouth?

- When do you swallow?

- How do the muscles of your throat contract to swallow the food?

- Give yourself plenty of time to savor every bite. Wait until you finish each mouthful before reaching for the next portion.

- With each bite, send gratitude to all the people who were involved in some way in preparing the food you are eating.

- Tune in to sense and feel what it is like to be in your body. Pay attention to all the flavors that are released and all the sensations in your body as you eat (and drink).

- Can you feel yourself becoming full?

- Does your body tell you when you’ve had enough sugar, starch, fat, or salt?

- What emotions do you feel?

You may find as you settle into the practice that your mind will have the tendency to wander off and automatic mindless eating habits may kick in. This is normal and part of the process, especially in the beginning. Simply notice this tendency and gently return to bringing mindful awareness to the experience of eating.

Mindful eating is like re-learning how to eat by appreciating your food and tuning in to your body. It can take time because you are slowing down each step of the process to pay full attention to it. But as you get used to appreciating each bite and tuning in to the signals from your body, you can start to eat mindfully at a more “normal” pace. Over time, mindful eating becomes intuitive. It becomes your natural way to eat.

I hope this article helps you mindfully enjoy your meals this holiday season!

Happy Holidays!